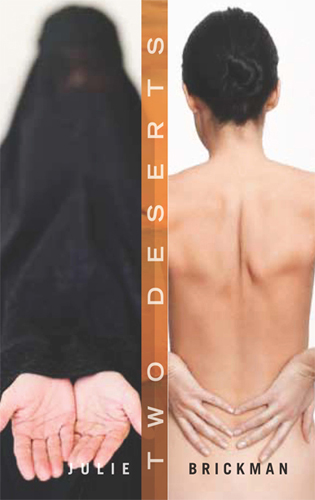

Two Deserts: Stories by Julie Brickman. As the title and cover suggests, two main characters—Emma and Livia—are the focus of these stories, and each is living in a desert, one literal and the other metaphorical. While this suggests a study of contrast, I found myself more impressed with the movement and energy in the story-telling. There is an enormous range of setting, topic, and conflict in these stories, and each story individually was compelling, fresh, and dynamic. The stories engage the reader because this energy and range—exemplified by the collection’s contents (below)—are mirrored in the prose. Brickman’s writing casts these story elements around the reader, ensnaring us in a web that is never predictable or linear. The writing, like the collection and women featured therein, is bold and fearless.

“The Night at the Souk” opens the collection with a headlong and fearless journey of Emma, a Westerner now working in the Middle East, as she seeks to melt into her surroundings and become one with these people she has studied so thoroughly.

“The Cop, the Hooker and the Ridealong” packs a punch because it weaves together several disparate, potent storylines: Livia, a psychologist who has worked for the police, is concerned that her neighbor might be violent; she recalls counseling a young sex worker who was brought into the profession by her mother; and Livia recounts her husband’s diagnosis of ALS/Lou Gehrig’s disease. The movement throughout these woven storylines is evocative, gripping, and creates a nice resonance.

“Message from Ayshah” is a letter to Emma from the Arab daughter of Emma’s employer; it’s a youthful and excited letter about a young woman’s admiration of this foreign business woman and her desires to see the world and break free from the constraints of her homeland’s customs.

“The Dying Husbands Dinner Club” is just what the title suggests, and Livia gets together with other women for support; the story is full of black humor and bittersweet unflinching honesty, also shared in “Gear of a Marriage”.

“An Empty Quarter” is about Samir’s mother (Samir being Emma’s colleague) as she tries to accept her son growing up, and a reflection on his being seduced into terrorism; this story is a study of many aspects of Middle Eastern culture, all within the point-of-view framework of Muslim Motherhood.

“Supermax” speculates on Ted Kaczynski, Ramzi Yousef, and Timothy McVeigh sharing yard time together in prison, and explored the psychology of very different terrorists.

“End of Lust” is a humorous (and almost pity-inspiring) poke at male chauvinism; by turns, this story is about a middle-aged man reaching emotional maturity, or a womanizer falling prey to feminism, or a story of impotence; it’s both a thought-provoking look at the politics and psychology of sexual relations, and a light-hearted jab at men’s libido and the world of academe.

In “The Rainbow Range,” Emma and tour guide Muhammad must rescue a lost tourist in the desert from the threat of quicksand.

“The Back of Her” contrasts Livia’s day-to-day struggles caring for her husband with her symbolic dreams of escape.

“The Lonely Priest” is about a gay priest in the Alaskan wilderness struggling to reconcile his faith with his earthly desires, in the wake of his adopted son’s suicide.